And in any case what is the use of an eccentric opinion, which never can hope to conquer the great agencies of publicity?

Bertrand Russell, On Being Modern-minded

Democracy and violence have been perceived to be connected since classical times (vide Republic 496c-e). According to S.E. Finer: “The Forum polity is comparatively rare in the history of government…Furthermore, most of them for most of the time exhibited the worst pathological features of this kind of polity. For rhetoric read demagogy, for persuasion read corruption, pressure, intimidation, and falsification of the vote. For meetings and assemblies, read tumult and riot.” Criticism has muted of late – democracy today has become a ‘creed’.

This essay envisions the possibility of a bureaucratic polity. The forum-bureaucratic polity has emerged in Europe and Japan. Such innovations in government are imperative for world peace. Implications of pathologies for development raised by Adrian Leftwich receive scrutiny. Having been sanctified, however, the forum polity has been rendered immune to empirical evaluation. Pathologies are deemed accidental, not essential. Violence for the sake of democracy has itself become legitimate.

‘…two women raped at gun-point in a hair salon; a bank robbed by five armed men; an elderly woman robbed at gun-point in her home; an unidentified dead body found in the street; security guards robbed by armed gunmen; two more security guards robbed at gun-point; one policeman shot dead; a man found murdered in his home; a couple robbed at gun-point in their home; a man robbed at gun-point; one dead body found; another dead body found in a park.’[I]

If this sounds like news from a Bangladeshi daily, guess again: these are (some) events in a day in the life of Johannesburg. But why the similarity?

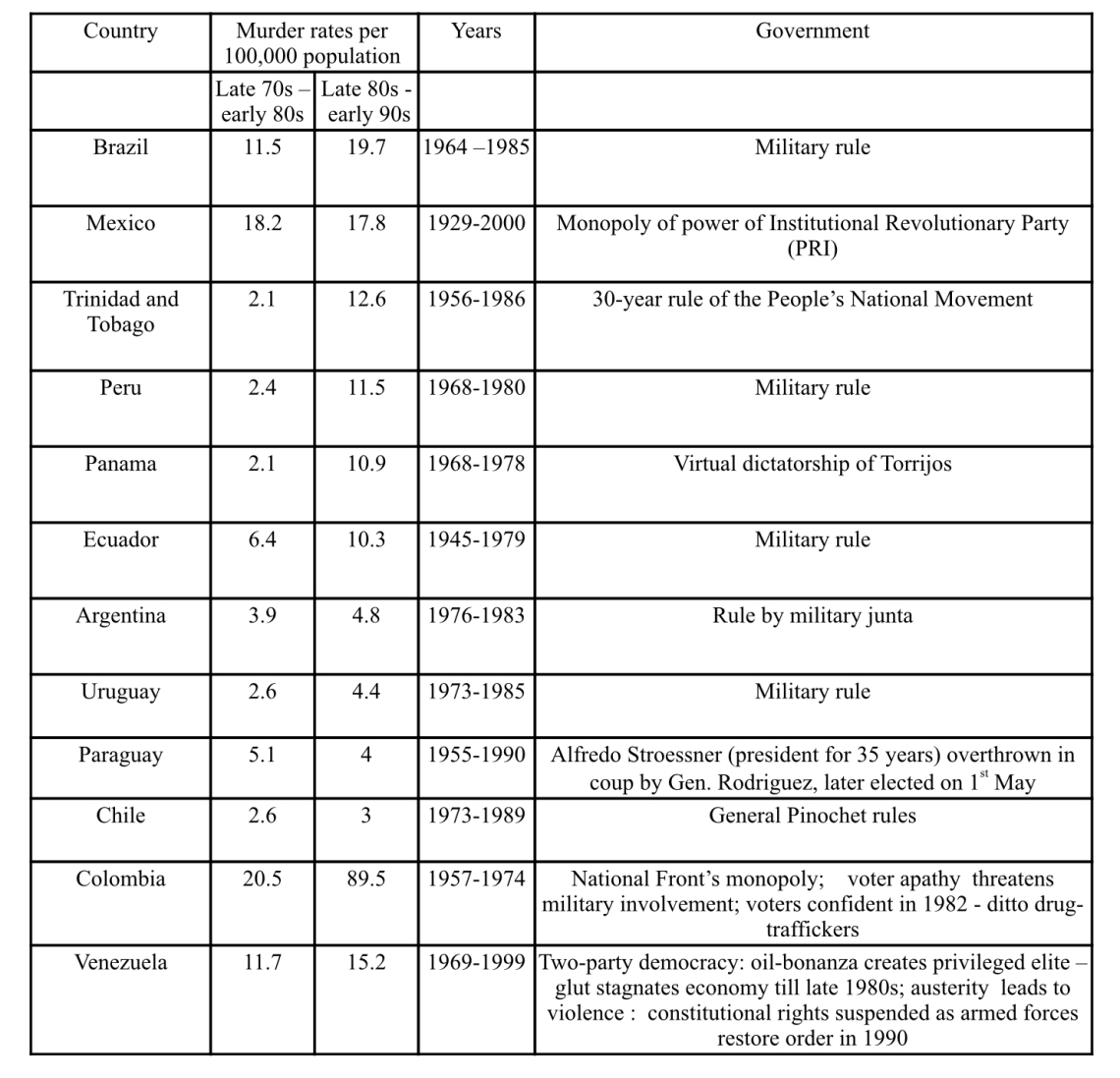

The reason is not far to seek, and recent history provides the answer. A casual glance at the experiences of Latin American countries ‘before’ and ‘after’ democracy reveals an explosive growth in crime and violence under democratic governments. In Trinidad and Tobago, there was a 500% increase in murder rates after the 30-year rule of the People’s National Movement ended in 1986; in Peru, after military rule ended in 1980, the increase was 379%; in Colombia, the end of the National Front’s monopoly in 1974 resulted in a 336% increase in the murder rate; in Panama, the figure had increased by 419% after the end of Torrijos’ dictatorship; in Brazil, 71%; in Venezuela, 30% (see table). These variations in figures betray an ineluctable pattern: an increase in criminal violence after the introduction of democracy in Latin America in the late 80s.[ii]

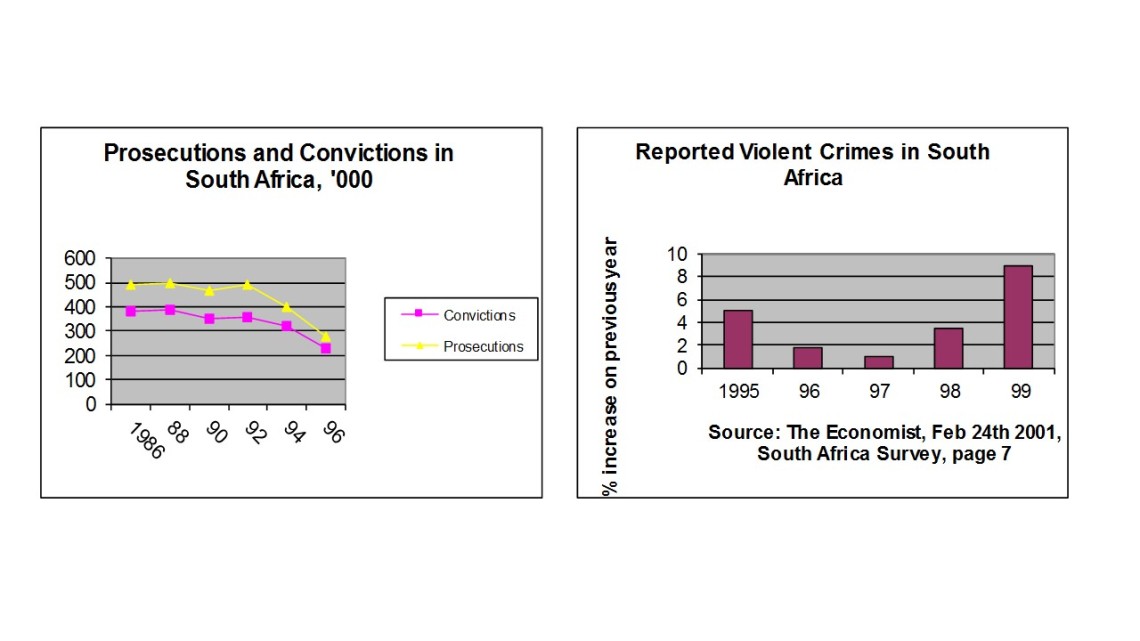

The murder rate in South Africa was seven times that of the United States – 61 per 100,000 – in 1996. That means that every day, on average, 71 people were being murdered. And the rate is a third higher than the national average in Guateng, the province centered on Johannesburg.[iii]

Under pressure, whites at first migrated to the National Party-dominated Cape Town; then finally began to leave the country in droves. 96% of South African emigrants are motivated to leave by the fear of violence, according to FSA/Contact, a market research group.[iv]

Nearly 39,000 – a definite underestimate – left the country between 1994 and 1997. And those who leave are the cream of society – skilled personnel coveted by such nations as America, Australia and Canada. No country, let alone South Africa, can afford brain drain on such a scale.

(The author may be misunderstood as endorsing the apartheid regime: coming from a part of the world that had been run by colonial masters, nothing could be further from the truth. The author merely points out that, had the transition to majority rule been a Ho Chi Minh-style takeover of the state – the ANCs original inspiration – and not a democratic transition, South Africa would have been spared the violence that plagues it today. In their analysis of the reasons for the violence, the authors Jean-Francois Bayart, Stephen Ellis and Beatrice Hibou are surely wrong.[v]

They attribute it to the anti-apartheid struggle and its aftermath: if so, then Vietnam should have been a very violent place after 1975! Neither would this view commit the author to totalitarianism: most Communist regimes are moving towards some kind of bureaucratic polity, a novel form of government discussed at the end of the essay.)

The Russian experience closely mirrors that of South Africa – except here, crime is already highly organised (South Africa is getting there, but more on that later). Organised criminal activity, to an extent, predates the transition to democracy and capitalism. The Brezhnev era’s incompetence bred two classes of deviant groups: a mafia that performed a useful social function by providing a black market in an otherwise centrally-planned economy; the other group was a throwback to the pre-Revolutionary gangster, the vory v zakone¬ – thieves-in-law. There were 20 criminal “brigades’ controlling Moscow, named after their area of operation. But theirs was a stable underworld – until democracy arrived.

In 1992, when Russia turned democratic-capitalist, these criminal hordes had the capital to buy up the entire state. They were too disorganised to do that; instead they fought among themselves, and raised the level of criminal violence in Russia.

However, the trend towards consolidation was well under way. In 1994, there were 5,800 criminal gangs in Russia. Violent competition has been pushing them into union. One notorious example was that of Vladimr Podiated, in Khabarovsk, locally known as ‘the poodle’ (euphemistically?). A man who had spent 17 years in prison camps for criminal offences, he has a firm grip on the city’s economy, has his own political party and television station and even has a letter from the Patriarch of the Orthodox Church sanctioning his altruistic credentials!

The evolution of the term ‘mafia’ since Soviet days is highly informative. Then, it stood for someone with money and connections. Now, it denotes an entire hierarchy, with the local illegal retailer at the bottom, his extortionist in the next level, who works for ‘Al Capone’ type businessmen in the next tier, up to the state. An estimated 30% to 50% of the Al Capone’s earnings finds its way up to the state-level. “The Moscow city authorities is the most corrupt government that has ever existed,” was the informed opinion of a clan-leader.

The evolution of the term ‘mafia’ since Soviet days is highly informative. Then, it stood for someone with money and connections. Now, it denotes an entire hierarchy, with the local illegal retailer at the bottom, his extortionist in the next level, who works for ‘Al Capone’ type businessmen in the next tier, up to the state. An estimated 30% to 50% of the Al Capone’s earnings finds its way up to the state-level. “The Moscow city authorities is the most corrupt government that has ever existed,” was the informed opinion of a clan-leader.

The judiciary is a carry-over from Soviet days; only now, their emancipation from the local party secretary, who had to be consulted before passing sentence, means that they are not accountable to anyone, and are free to take bribes. Those with grievances prefer razborka (mafia-talk for rough justice) to the courts. As to the legislators, their favourite game is to stymie government at every step to prevent the passage of effective laws. The laws serve to lock up the innocent without trial indefinitely, and to let the guilty get away with it. The police? Thoroughly corrupt.

Life for the ordinary Russian, the man-in-the-street, has meant greater uncertainly and insecurity. Whatever he earns, he wants to stash abroad. A businessman was reported as saying that fear of the mob has stunted his aspirations: he will not advertise; he won’t go into oil trading – too risky; he won’t set up an attractive office lest he attract the wrong kind of people – “the criminal and state mafias”. Things were different in Soviet days; The Economist acknowledges the fact that “the rate of crime has risen fast in Russia, but from a low base.”[vi]

The identical pattern emerges from Malawi to the Philippines. In the latter country, the death penalty had been abolished in 1986. It was re-introduced in 1995, and enthusiastically backed by judges as well as the Roman Catholic population. The new death penalty covers rape, incest, drug trafficking and murder.[vii]

The identical pattern emerges from Malawi to the Philippines. In the latter country, the death penalty had been abolished in 1986. It was re-introduced in 1995, and enthusiastically backed by judges as well as the Roman Catholic population. The new death penalty covers rape, incest, drug trafficking and murder.[vii]

Several sexual murders created the momentum for its popular re-introduction. In Malawi, donors forced the former dictator to call an election in 1994. Since then, mugging and violent crime have soared.[viii]

Since the successful conclusion of ‘Operation Restore Democracy’ in 1994 by America in Haiti, the Americans’ main concern has been less about democracy than the collapse of government, and with it, rising crime, violence, and – most relevantly for the Americans – re-export of drugs from Haiti to the United States.[ix]

The 25-year-rule of Lynden O. Pindling ended in the Bahamas, and his Progressive Liberal party became the opposition, in 1992;[x]in a move familiar in Bangladesh, he was accused of involving students in politics. Crime has become an election issue and the Bahamas – like the Philippines – has started hanging people after a gap of 14 years. In Nepal, politics is becoming criminalised, even as the police has become politicized.[xi]

On the sixth anniversary of the start of the Maoist’s “people’s war” on February 16th, 2002, 153 policemen, soldiers and civilians were killed by rebel troops. The Maoists took to arms when they felt that the political process was ignoring them – perhaps encouraged by leftist violence against landowners in the Indian state of Bihar across the border.

In their first four years of armed struggle, the Maoists were the less efficient side. They have improved considerably. The conflict has clearly brutalised Nepalese society. In 2000, the government admitted to the police killing 436 people the previous year. Four years into the uprising, 5000 people were arrested, of whom many have disappeared or been tortured. [xii]

In November 2001, a state of emergency was declared to enable the army to engage the rebels. Since then, the army has had more success: in early May 2002, it killed 550 Maoists.(George Bush’s administration has asked Congress to authorise 20 million dollars in military aid to Nepal).[xiii] In Kenya, the rich and entrepreneurial Asian minority began a South Africa-style exodus – their age-old connection with the ruling party exposed them to threats from the opposition, while the government said it could do nothing to protect them from increasing gangster violence.[xiv]

Today’s violence in Jamaica has its origins in the political conflicts of the 1970s, when both the Jamaica Labour Party and the ruling People’s National Party used rival gun gangs that tore the nation apart: the continuing battles have raised demands for a South Africa-style ‘truth and reconciliation’ commission, an idea rejected, unsurprisingly, by both sides.[xv]

In Nigeria, ethnic and religious violence has escalated since the democratic transition – ditto Indonesia. Since Nigeria returned to civilian rule in May 1999, more than 6,000 people have died in ethnic and religious violence fomented by vote-hungry politicians.[xvi]

In Taiwan, gangsters have penetrated parliament, and, as Lee Kuan Yew observed, Taiwan’s elections have been condemned for the use of gangsters.[xvii] The murder rate in Brazil has soared since military rule ended (see first table). Today, it is even higher: 27 per 100,000.[xviii] However, the average for Brazil conceals the violence of its major cities. The level of effective policing is so low that robbers and drug barons go on killing sprees with impunity. A study of 290 cases of fatal shootings of children and adolescents in 1991 by the Violence Studies’ Group of Sao Paolo University found that only five of these cases had led to conviction![xix] It is small wonder then that polls conducted in 1994 in Rio de Janeiro showed that 80% of the citizens wanted the army back on the streets to control crime.[xx]

The democracy of Israel was established at the expense of the Arab majority of Palestine – the minority that remained after most Arabs became refugees were granted political rights, an act that permitted Israel to burnish its credential as a democracy, which, however, has not compensated for perceptions of illegitimacy. Since inception, the democracy has been the focus of violence throughout the Middle East.[xxi]

And, of course, the democratisation of Yugoslavia has unleashed some of the worst violence in recent memory.[xxii] The ‘Portrait of Tito’ (1964) by Norman Rockwell, showing Tito in the foreground, and Serbs, Croats and Bosnians each facing grimly away from the other, in the background, was prophetic of the coming carnage (The Saturday Evening Post refused to carry the endorsement of a communist leader on its cover).[xxiii]

But it is in Central Africa that the death toll has been highest since the post-Cold War transition to democracy. After independence, the Tutsis retained power in Burundi, but in Rwanda the Hutus led the new government. The latter were a majority in both countries. In June 1993, Melchior Ndadaye – a Hutu – won Burundi’s first democratic election ‘by virtue of being a member of the biggest tribe in a country where a free vote naturally meant a vote along ethnic lines’,[xxiv] as one newspaper observed. In October, 1993, Ndadaye was murdered by the Tutsi-dominated army. Over 100,000 people were killed in the subsequent massacre. Ethnic strife? According to David Reynolds: ‘But as we shall also see in Yugoslavia, ethnicity is rarely a spontaneous force. It needs to be manipulated by politicians. What mattered in Rwanda was the reaction of Hutu hard-liners in the party and the army to their impending loss of power’.[xxv]

General Habyarimana, since grabbing power in a bloodless coup, had run the country for 21 years. Tutsi rebels fleeing to Uganda had formed the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) and invaded Rwanda in 1990. Under the 1993 peace deal both sides agreed to form an integrated army and to share power in a new national government. Paul Kagame, the rebel leader, in an echo of the words of David Reynolds, said during the fatal week that the killings “had been wrongly portrayed as ethnic strife. It is clear these acts of murder are political”.[xxvi]

Hard-liners shot down Habyarimana’s plane on April 6th, 1994, and a well-planned program – similar, as we shall see, to the ones in India and Sri Lanka in 1983, 1984 and 2002 – ensued. 800,000 Tutsis were butchered. The RPF captured the country, and 2 million Hutus fled, mostly to Zaire. In Burundi, a Hutu-led coalition that had won power in the 1993 election was overthrown by a Tutsi-led coup in July 1996. Both Rwanda and Burundi, 80% Hutu, were now controlled by Tutsis. ‘For Tutsis after 1994, “democracy means death”’ observes David Reynolds.

The Tutsi-led government in Rwanda was afraid that the Hutus in Zaire (now Congo), sheltered by Mobutu Sese Seko, would rearm and return. Rwanda organised a rebellion and toppled Mobutu. They replaced him with Laurent Kabila, who turned against his backers and armed the Hutus. Rwanda tried, and failed, to topple him, despite help from Uganda and Burundi – Angola and Zimbabwe, among five nations, came to Kabila’s rescue. Nine national armies and their rebel proteges shot, hacked and starved over 3 million people to death in Congo.[xxvii]

The end of a 21-year dictatorship in Rwanda, therefore, led to the death of nearly 4 million people!

Much of sub-Saharan Africa had been violent even before the democratic transition of 1989-92. However, what we perceive is a widening of the area of violence As Jean-Francois Bayart, Stephen Ellis and Beatrice Hibou have observed in their book The Criminalization of the State in Africa: ‘…it must be said that the list of war-torn countries south of the Sahara has tragically lengthened in recent years…and may still see further additions….”[xxviii]

And indeed that has been the case. Nigeria – where 6,000 politically-motivated murders have taken place since the 1999 election – has already been noted. A few more examples will suffice. Since the election of 1992, there have been three civil wars in Congo-Brazzaville – and a fourth one seemed to be brewing in April, 2002. The losers in the elections refused to accept defeat, and 800,000 people were internally displaced. This time 50,000 have fled the Pool region, the violent outpost of Pasteur Ntoumi and his ‘Ninjas’. An informal truce – he refused to sign the 1999 peace accord with president Denis Sassou-Nguesso – appears to be unraveling.[xxix]

A refusal to accept defeat also resulted in a near-civil war in Madagascar. For six months in 2002, after an indecisive election, there were two claimants to the presidency – Didier Ratsiraka, the incumbent, and Marc Ravalomanana, the mayor of Antananarivo. The former was backed by much of the army and four of the country’s six provincial governors, with some of the top brass and the gendarmes backing the latter. The dark-skinned coastal citizens with ties to Africa – who have usually had enough votes to put one of their own into the presidency – were pitted against the light-skinned highlanders of Asian descent. Mr. Ratsiraka blockaded the other half of the country from his coastal stronghold. Several bridges were blown up and several hundred people killed. Mr. Ratsiraka finally fled and France and the United States recognised Mr. Ravalomanana, although the African Union called for fresh elections.[xxx]

Fear of losing votes have brutalised, in addition to Burundi, Rwanda, Congo-Brazzaville, Madagascar and Nigeria, Kenya and Zimbabwe as well. Employing thugs and state power, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe stole a presidential election in March and has been intent ever since on punishing white farmers for (so he believes) financing his opponent, Morgan Tsvangirai’s, campaign by redistributing their land to his cronies.[xxxi] Daniel Arap Moi of Kenya either buys votes or inflames ethnic divisions. According to Transparency International, the ruling party, KANU, has transformed self-help groups called harambees, where money was traditionally donated for community projects, into instruments for purchasing votes. In 2001, he proclaimed that tenants (mainly from the Luo tribe) should not pay high rents to their (mainly Nubian) landlords. The former began fighting the latter: if Kenyans vote along tribal lines, Mr. Moi stays in power by giving members of each major tribe cabinet posts. Meanwhile, rapists in high places are tolerated.[xxxii] Increasingly, and inevitably, crime has become organised. We have seen how the Russian mafia has forged a symbiosis with the state. A survey by the World Economic Forum has found that Russia, Colombia and South Africa are in the bear hug of organised crime. Consequently, there is little the South African police chief can do about it. The ending of apartheid opened a crack in the edifice of the state, a crack that became an open door for organised gangs from as far athwart the world as China, Colombia and Nigeria – and Russia. The thug who robs people and their homes at gunpoint is at the bottom of a hierarchy. He delivers the goods, takes his cut and, after that, the big guys take over. In 1996, the police knew of 481 criminal syndicates that smuggled drugs, guns, diamonds, rhino horns and luxury cars.[xxxiii] The south of Florida has become a haven for organised crime. Gangs originate from Jamaica, Colombia, Italy and Russia. After a three-year investigation, the US Drug Enforcement Agency uncovered an alleged trafficking organisation that transported cocaine from Ecuador to St Petersburg in cargoes of iced shrimp. In 1997, they were on the verge of buying a Russian navy submarine to ferry cocaine up the west coast of the United States to San Francisco![xxxiv]

It is no coincidence that for the first time since 1983, crime in Argentina became an electoral issue – 1983 was the year that rule by the military junta ended. Taxi-drivers robbed passengers, burglars shot people in their homes, and the education minister got mugged. Eduardo Duhalde, the presidential candidate in 1999, promised ‘zero tolerance’ as enforced in New York, as well as – you guessed it – capital punishment. Martin Abregu, director of a human-rights group that monitors the police, observes that criminals have become obviously more violent. Regarding the quick-fix solutions on offer from politicians, Mario Ciafardini, national director of crime policy at the justice ministry, says: “Issues of social strategy can’t be resolved in a year. They require permanent effort.’

But perhaps there’s a reason why politicians are uninterested in permanent effort. Although crime is more frequent than the statistics say – less than a third are reported, and of these only about 1% are cleared up – the police alone cannot take the blame. Policemen are expected to connive at prostitution, illegal gambling and the rest; whistle-blowers lose their jobs, or worse. The money is passed on to the top. Huge sums are involved. Judges covering a case revealed that six stations raised over $3m a month. There’s a chain beginning from the man on the beat to his superiors and then to divisional superintendents. Does it stop here? Unlikely. A senior policeman observes, anonymously: “At election time, the pressure to raise money increases”.[xxxv]

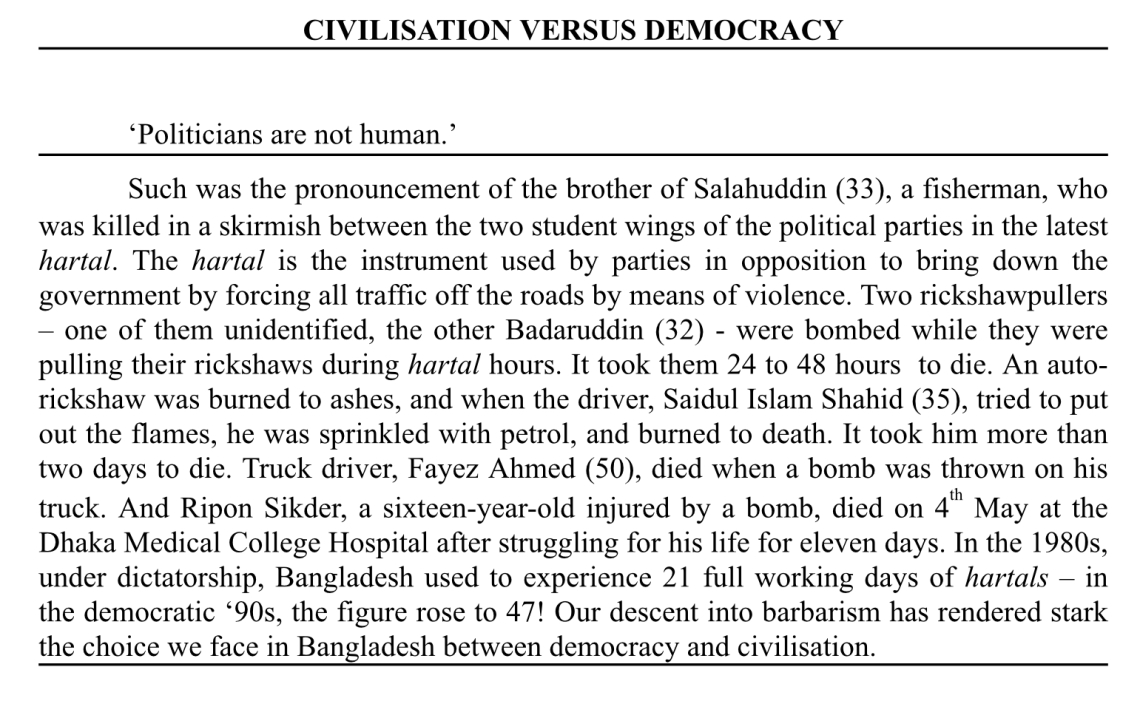

The economic costs are enormous. For Latin America, as a whole, its income would be 25% higher if it had been like other regions in terms of safety, reckons the World Bank. According to Mauricio Rubio, an economist at Bogota’s University of the Andes, violence costs Colombia 2% points of growth per year in terms of lost tourist revenue and foregone investment.[xxxvi] In Russia’s case, one has only to look at the size of foreign investment in Finland – used by entrepreneurs as a (much safer) point of entry into the Russian economy – to appreciate the staggering cost that violent crime imposes.[xxxvii] Capital flight is taking place in South Africa – human capital. 11% of the top managers and 6% of the middle managers who resigned in 1997 did so to emigrate. That’s a lot of talent for a poor country. In Bangladesh, economic shutdowns enforced by means of violence by political parties have more than doubled since the democratic transition. These hartals, as they are called, cost the country $50 million per day. According to the World Bank, 5% of GDP per year is lost due to hartals (see last box entitled Democracy versus Civilisation for a description of hartal).[xxxviii]

The economic costs are enormous. For Latin America, as a whole, its income would be 25% higher if it had been like other regions in terms of safety, reckons the World Bank. According to Mauricio Rubio, an economist at Bogota’s University of the Andes, violence costs Colombia 2% points of growth per year in terms of lost tourist revenue and foregone investment.[xxxvi] In Russia’s case, one has only to look at the size of foreign investment in Finland – used by entrepreneurs as a (much safer) point of entry into the Russian economy – to appreciate the staggering cost that violent crime imposes.[xxxvii] Capital flight is taking place in South Africa – human capital. 11% of the top managers and 6% of the middle managers who resigned in 1997 did so to emigrate. That’s a lot of talent for a poor country. In Bangladesh, economic shutdowns enforced by means of violence by political parties have more than doubled since the democratic transition. These hartals, as they are called, cost the country $50 million per day. According to the World Bank, 5% of GDP per year is lost due to hartals (see last box entitled Democracy versus Civilisation for a description of hartal).[xxxviii]

The last paragraph – on the connection between democracy and development – prompts one to reconsider these words by Adrian Leftwich: “….development cannot simply be managed into motion by some idealised system of good governance, evacuated from the world of politics. For neither democracy nor good governance are independent variables which have somehow gone missing in the developing world: they are dependent ones. And whatever their relationship with economic growth and development may be, both are the products of particular kinds of politics and can be found only in states which promote and protect them. Indeed, they are a form of politics themselves and not a set of institutions and rules….Indeed, to insist on democratic institutions and practices in societies whose politics will not support them and whose state traditions (or lack of them) will not sustain them may be to do far greater damage than not insisting on them. Moreover, the kind of political turbulence which such insistence may unleash is bound to have explosive and decidedly anti-developmental consequences.”[xl]

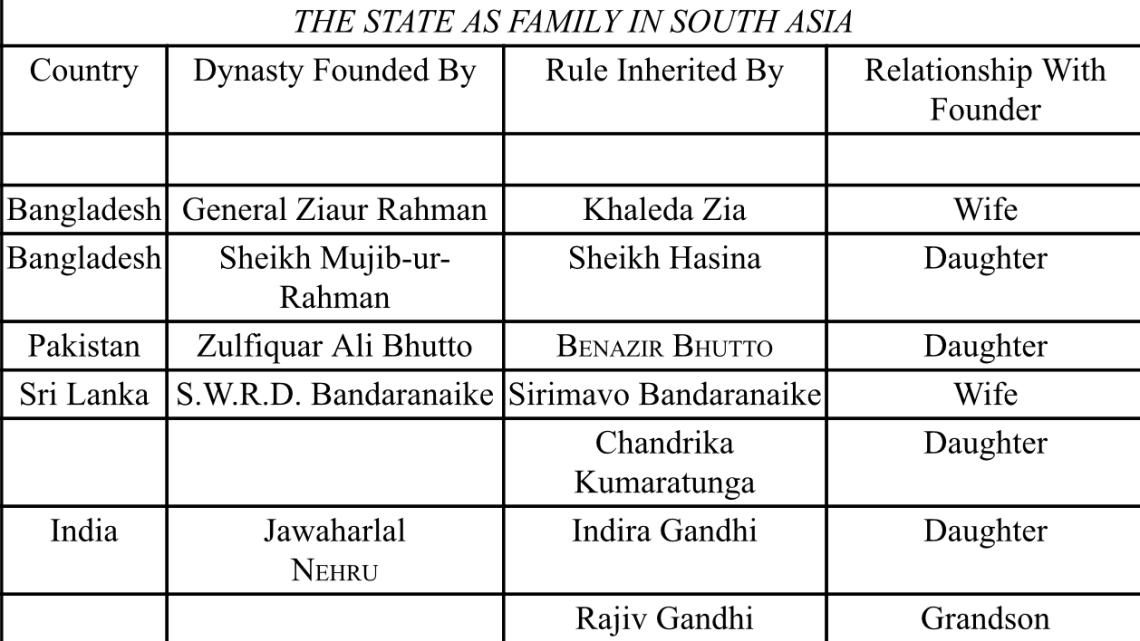

And then there’s India – the world’s biggest democracy. A biographical approach best illustrates the complex tangles of Indian politics and Indian crime. In 1981, Phoolan Devi and her cohorts were accused of slaughtering 22 upper-caste men, who, she claims, had gang-raped her, in the hamlet of Behmai in Uttar Pradesh. She denied the accusations, but agreed to surrender to the police in 1983 by agreeing to the 70 different counts of extortion, kidnapping and murder outstanding on condition that she spend only 8 years in jail. In the event, she spent 11 – then the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh dropped the charges, and took her into his party! She went on to become MP.

According to the police, of the 85 MPs from Uttar Pradesh, at least 28 had criminal records or serious charges against them in 1997.[xli] Indira Gandhi introduced goons to politics to get votes; since then, they have gone into politics for themselves.[xlii] The connection between politicians and the Bombay underworld, for instance, is well known. And violence against the 160 million untouchables has been increasing.[xliii] (But more on India later.)

And yet Japan is also a democracy with some of the world’s lowest figures for crime and highest for crime detection. The difference between Japan and India is that Japan has ‘Asianised’ – bureaucratised – democracy: the Liberal Democratic Party has been in power for nearly 50 years, and it is the bureaucrats who run the country. And these bureaucrats have been – bar a few major lapses – remarkably close to the people. True, Japan does have organised crime, but the level of violence is so low as to leave the average citizen feeling – and actually being – perfectly safe.

Japan has a conviction rate of 99.8% despite the fact that, in 1990, 31% of offenders were released after signing an apology. But these were for minor offences; for major offences, the Japanese police only strike when they’re absolutely certain. Most convictions are obtained by means of – unconstitutional – confessions. On the other hand, non-offenders love the police! The emphasis is on crime-prevention with policemen spread out across the country in boxes to offer help (including personal loans!). In 1991, there were 188,000 requests for personal advice. A third related to crime-prevention, over a quarter to family problems, and around a fifth to other matters, like personal finance. The number of articles returned to the police (4.1m) exceeded the number reported lost (2.9m). 18.5 billion yen ($137 million) of lost cash were handed over by friendly citizens.[xliv]

The Japanese style of policing – and Japanese political culture – explains why Japan has both one of the world’s lowest rates of violent crime as well as one of the lowest rates of incarceration (see table),[xlv] despite an economic downturn lasting well over a decade!

Why does democracy outside its civilisation of origin – Western Europe and the Anglo-Saxon countries – degenerate into violence?* The answer lies in our experience of government. A thousand years separated the resurrection of the state in Western Europe from its collapse with the western Roman Empire. In this lacuna of government, all the later forces that would challenge the authority of a king – clergy, nobility, bourgeoisie – were formed.[xlvi] Such hiatus in government is unique to the western world. The rest of the world has never had to learn to do without a centralised authority[xlvii] before the colonial conquerors introduced ideas of representative government. Democracy, in short, is alien to Asia. It is also alien to the Iberian ‘civilisation’ where Visigoths, Muslim rulers, and the absolutist Habsburgs and Bourbons preserved the continuity of the centralised state.[xlviii] Spain and Portugal were dictatorships until only the other day, in historic terms. (Induction or the promise of induction, into the European Union has kept many an aberrant state on ‘good’ behaviour). Consequently, when the state loses its monopoly of power, and becomes parcellised into political parties, it begins to collapse.

Why does democracy outside its civilisation of origin – Western Europe and the Anglo-Saxon countries – degenerate into violence?* The answer lies in our experience of government. A thousand years separated the resurrection of the state in Western Europe from its collapse with the western Roman Empire. In this lacuna of government, all the later forces that would challenge the authority of a king – clergy, nobility, bourgeoisie – were formed.[xlvi] Such hiatus in government is unique to the western world. The rest of the world has never had to learn to do without a centralised authority[xlvii] before the colonial conquerors introduced ideas of representative government. Democracy, in short, is alien to Asia. It is also alien to the Iberian ‘civilisation’ where Visigoths, Muslim rulers, and the absolutist Habsburgs and Bourbons preserved the continuity of the centralised state.[xlviii] Spain and Portugal were dictatorships until only the other day, in historic terms. (Induction or the promise of induction, into the European Union has kept many an aberrant state on ‘good’ behaviour). Consequently, when the state loses its monopoly of power, and becomes parcellised into political parties, it begins to collapse.

The lesson for a country like Bangladesh – where headlines such as “Cases of gang-rape on increase in rural areas” (The Observer, 3rd November 1998) are sickeningly common nowadays – is clear. If we want a safe society we must abandon the democracy that has been foisted on us by foreign donors. In India’s 50 years of democracy, crime has become firmly enmeshed in the fabric of the state, so much so that the – unelected – judges on the Supreme Court repeatedly find it necessary to order investigations of – elected – representatives of the people. Such a damning indictment of democracy holds invaluable insights. Elite crimes have deliberately not been investigated with diligence. In 1998, the chief justice J.S.Verma sought to remove political and bureaucratic meddling with the Central Bureau of Investigation and the Enforcement Directorate by making the Central Vigilance Commission – their supervisor – a statutory body.[xlix] State-sponsored religious violence goes unchecked. (A letter to the editor in India Today begins thus: ‘Indian politics is currently represented by politicians who have little or no education but boast of sound criminal backgrounds’).

It was ever so. In Leveling Crowds: Ethnonationalist Conflicts and Collective Violence in South Asia, anthropologist Stanley J. Tambiah revealed how democracy and ethnonationalist violence are causally connected in the whole of South Asia. From the Sinhalese-Tamil riots of 1956 to the 1984 riots in Delhi and the post-Babri Masjid one in Bombay, the author establishes that ‘…participatory democracy, competitive elections, mass militancy, and crowd violence are not disconnected.” He adds: “They were not disconnected in Europe: in Britain, for instance, the latter part of the nineteenth century saw the parallel rise of democracy and industrial militancy….And before that the French Revolution had ushered in the crowd as an enduring political force….”[l]

The latest World Development Report on poverty describes empirical studies showing correlation between newspaper circulation, the level of democracy and crisis resolution. The model is something like this: there is an event (drought or flood); newspapers report the event; politicians respond to the event because they are responsible to the electorate.[li]

Since most Indians do not read newspapers (national circulation of dailies in 1998 was 58 million[lii]), and that a country like Iran, which neither has a free press nor a democratic form of government and yet responds to crises such as earthquakes with admirable alacrity, the model would appear to be inspired more by the researchers’ ideological leaning than the facts of the matter. Nevertheless, let us assume that the model is faithful to reality.

Now, let’s take an event of a different nature: say, killing by members of a minority (such as, the murder of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh guards or that of 13 soldiers by Tamils). Newspapers report the event; politicians react. How do they react? According to Stanley J. Tambiah: “Even when the suddenness and the emotional trauma of Indira Gandhi’s assassination are taken into account, the evidence is clear that…the destructive actions of the mob…were encouraged, directed, and even provisioned by Congress (I) politicians, activists and supporters, and indirectly aided by an inactive, cooperative police force.”[liii] There is a striking similarity between the anti-Sikh riots of 1984 in India and the anti-Tamil riots of 1983 in Sri Lanka.

It cannot be over emphasised that nuclear weapons have added a nightmarish dimension to the responsiveness of politicians to perceived threats reported by the media. But more on that later. Meanwhile, we observe that an earthquake did occur in India, and that it was badly handled by the politicians. However, the politicians responded to another event with greater agility – the killing in Godhra of 58 Hindus returning by train from Ayodhya on February 27, 2001 by Muslims angry with the Hindu Right’s decision to demolish a mosque at Ayodhya and replace it with a Hindu temple (Godhra had seen Hindu-Muslim riots in 1947, 1952, 1959, 1961, 1965, 1967, 1972, 1974, 1980, 1983, 1989, 1990, and 1992). What followed in Gujarat was a government-backed pogrom centred mostly in Ahmedabad, and indistinguishable from the anti-Sikh and anti-Tamil riots described above. According to Frontline:

In less than 12 months, Gujarat’s Hindu Right will face Assembly elections. Discredited by its record on the economic front, and its less-than-creditable handling of the 2001 Kutch earthquake, few people had given the Bharatiya Janata Party a serious chance to retain power. Now, after February 28, the Hindu Right is again on a roll. It has learned the lessons of the 1998 Lok Sabha elections when a string of attacks on Christians and Muslims in south Gujarat helped the BJP wrest key seats, including Godhra, from the Congress(I)….

For decades, riot after riot has pushed the city’s Muslims into deprived ghettos. After February 28, they have become Bantustans. Terrorising Muslims is no longer a vote-driven political enterprise. It has become state policy.[liv]

And in the elections, as Kuldip Nayar, an Indian columnist, pointed out, Chief Minister of Gujarat Narendra Modi “did best in the area where he planned and executed ethnic cleansing” – a swing of 18 per cent in central Gujarat and 11 per cent in the north. Altogether, the BJP won 126 seats in the 182-member assembly.[lv]

Two consequences of democracy must be kept in mind: the distaste for centralised government, and its representative nature. Any centralisation of power is resented by the democrat; such a state of affairs is described by him as “loss of liberty”. Furthermore, anyone who is not represented in a democratic state – such as slaves – will be, at best, neglected, and, at worst, abused. ‘Representation’ is used broadly here, to mean ‘effective representation’, and includes pressure groups, which can use their financial and organisational prowess – their social capital, in short – to wield influence totally disproportionate to their numbers.

These observations explain much about contemporary events. Terrorist attacks in the United States – whether the work of domestic far-right groups, or overseas agents – have been generated by the nature of American democracy. A state that is under pressure – both from the electorate as well as from interest groups – to intervene in far-flung places will be resented by strangers. At the same time, citizens will find such a powerful state inconsistent with the ideal of democratic participation (for historical reasons, the view of the state as enslaver and threat to liberty is not shared in Asia, as was pointed out above). America will therefore be despised both from within and from without. In fact, the state becomes a target for any unrepresented ‘constituency’, internal or external. And both sets of constituencies will use their social capital to launch such an attack. Timothy McVeigh, recently executed for the bombing of the federal Oklahoma building on April 19th 1995 which claimed 168 victims, stands for the inner threat. He maintained that he was ‘a soldier in a state of war with the federal government’.[lvi]

Highly efficient pressure groups, on the other hand, can wield the entire apparatus of the state against an unrepresented people. The Jewish and Cuban-American lobbies come readily to mind; so do the farm and steel lobbies, for instance. Blacks in the United States, however, have had to riot on many occasions to make their presence known to the majority – notwithstanding the efforts of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People. (The under-representation of African-Americans in the American political decision-making process is underscored by some stark statistics: though only 12% of the population, by 1990 blacks had come to represent over 44% of prison population – in 1994, 7% of all black men were behind bars, compared to less than 1% of white men. Since incarceration deprives one of the right to vote in the most populous states, and since prisoners are usually prevented from voting, African-Americans have been significantly disenfranchised).[lvii] Blacks are not ‘effectively’ represented.

And neither are most foreign peoples. As James Zogby of the Arab-American Institute observes: “When we do focus groups, Americans say, ‘I know who the Israelis are, I don’t know who Palestinians are.’ And they sympathise and identify with the one they know.”[lviii] Hence, we come across such chilling passages as the following in an international newspaper like The Economist:

‘The last presidential election saw about 4m evangelical conservatives, once reliable Republican voters, staying at home. Mr. Bush may be able to re-engage evangelicals by getting cloning banned. But this will count for nothing if they conclude that he is putting pragmatism above principle on Israel, a country evangelicals revere both as a home for God’s chosen people and as the scene of the “end of days”. The stakes are particularly high because the impending ban on soft money, which will kick in after the November elections unless it is ruled unconstitutional, will make the Republican Party far more dependent on the sort of small donations that come from grass-roots activists.

‘The make-or-break issue for Mr. Bush, however, will be Iraq. Mr. Bush aroused huge expectations on the right when he promised to confront the “axis of evil” and extend the war against terrorism into a war against heavily armed toxic states. He has repeatedly stated his determination to mount a war against Saddam Hussein to damp down criticisms of his Middle East policy.’[lix]

Those who find democracy an attractive form of government should keep in mind those who are not represented, but affected, by such a form of government – the victims of democracy.

The response of the American government to the events of September 11th has been a typically democratic response. We noted above the model of democratic responsiveness espoused by recent researchers: event-report-response. In this case, the event was the attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon, reported in real time by the media, and the political response was the sanction of war against a nation for harbouring the suspected perpetrator. Only one member of Congress voted against military action, and she was given extra police protection at the Capitol.[lx]

The similarity with the war in Chechnya cannot be overemphasized. When several bombs went off in Moscow, the Chechens were suspected. The subsequent bombing of Chechnya was a classic democratic response, and proved so popular with the electorate that Vladimir Putin won the presidential election on the strength of his belligerence.[lxi]

Unsurprisingly, crime and violence have become accepted – and to that extent, legitimised. The legitimisation of violence is the most frightening aspect of democracy in the countries discussed here. The election of criminals and those with criminal connections legitimises crime – after all, how can the people be wrong? Everywhere the feeling is: such things will be, and there’s nothing we can do about them. A few determined groups try to do something about them – they are the vigilantes. That is why, along with headlines such as “Cases of gang-rape on increase in rural areas” mentioned above, we also get headlines of another kind: “Dacoit beaten to death in Sonagazi” (same paper, same day). And self-redress has been springing up from South Africa to Russia, which is just another turn of the same screw.

The moral ambiguity surrounding such ‘spontaneous vigilantism’ in Bangladesh can be gauged from this editorial in the local paper, The Daily Star:

“ [The] Catching [of] an alleged mugger and setting him on fire by pouring kerosene all over his body at Mirpur last Monday night raked up a nightmarish memory. We can’t forget that not so long ago lynching became (sic) a regular occurrence just about anywhere in the country. But mostly alleged muggers would either be burnt to death or set on fire by angry crowds in broad daylight in the capital city….

“Police said there was no case against him, though the local people alleged that he was involved in criminal activities. Therefore, it is only natural for us to wonder whether he was a victim of enmity. It is not impossible for anyone to frame someone and instigate the onlookers against that person. We have seen how ugly mob temper can get in such situations. But we are yet to know for sure whether all those who had been lynched earlier on were real criminals or several of them were just victims of circumstances.”[lxii]

Between 2001 and 2003, more than 150 people have been killed by mobs in the capital city alone.

Seemingly in recognition of the escalation of violence beyond the limits of public tolerance the government of Bangladesh passed the ‘Public Safety Act’. This has been widely condemned as redundant and repressive. The most controversial aspects of the law have been the denial of bail for three months during which investigation must be completed and the validity of the testimony of witnesses absent at trial without, therefore, being subject to examination and cross-examination. According to a lawyer, the result is that the breaking of a car window can lead to rigorous imprisonment for two years!

It has been widely suspected that the real motive of the ruling party is not to curb crime but to harass the opposition. In fact, the breaking of car windows is one of the methods by which the opposition exert pressure on the government by keeping all traffic off the roads – a phenomenon known as the hartal.

In fact, a clear pattern emerges. ‘Repressive’ laws have been passed during each democratic government since the birth of Bangladesh. Every time, there has been the same excuse for passing these laws – violence. That has presented the ruling party with the opportunity; the motive has been to curb – or even eliminate – the opposition. Remarkably, none of the military governments have ever needed to pass a law curtailing fundamental rights – the motive and the opportunity were equally absent.

That the prospect of law and order improving even under the present law is dim is proven by the nature of the offences and offenders. The following excerpts from local newspapers illustrate:

‘In an obvious show of strength yesterday, Haji Moqbul, MP from city’s Mohammedpur-Dhanmandi constituency, led a motorcade of more than 10 cars and a couple of minibuses at around 11:30 am. As his convoy reached the intersection of Mirpur Road and Green Road, it confronted a group of BNP [Bangladesh National Party – the opposition] activists on the run after being chased by police….

‘The armed men caught two young men and started to drag them towards the motorcade that waited on the Mirpur Road. At one point the men hit one of the captives in his head with a revolver and shot another in the chest point blank, witnesses said. A policeman who was leading a dozen men in riot gear stood silently nearby.’[lxiii]

‘Two people were shot dead and 10 others injured in a gunfight between two rival factions of Awami League in Sandwip today….

‘The two factions – one led by local MP Mostafizur Rahman and the other by then (sic) AL President Shahjahan, fought with guns and home-made bombs for establishing (sic) supremacy in local politics, police sources said.’[lxiv]

Much of the violence is caused by the ruling party itself, against whose members such laws are most unlikely to be applied. Since the last election, in which the governing Awami League lost heavily, and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party along with three other parties won most of the seats, the violence has been the act of the student bodies of the latter against supporters of the former, including the Hindu minority that traditionally votes for them. Amnesty International Secretary General, Irene Z. Khan, took up the issue with the government when she was in Bangladesh.[lxv] However, it is clear that Amnesty is merely looking at the symptoms of a deeper malaise, if the central idea of this essay is correct.

The foot-soldiers in this democratic war are the students. It was a group of students that – with assistance from the donors – overthrew the last dictator, General Ershad. Tellingly, General Ershad had no student body in his political machinery. A violent student army is essential for political parties to survive the agitation of the opposition – and to get even. As The Daily Star observed: “Immediately after a party serves out its tenure in government, its rivals invariably go on the offensive to settle ‘old’ scores. And, as a matter of practice, the battle line is drawn first at different universities and colleges.”[xlvi]

In microcosm, the Tejgaon Polytechnic Institute’s recent history of killings[lxvii] and revenge-killings among students illustrates the national problem. The students are used by political leaders to collect huge amounts of money through extortion: these are known as ‘tolls’. They are collected under duress from shops, businesses and local residents. Part of the money finds its way to the political parties and part is used to finance the reckless, high-spending, drug-filled lifestyle of stressed-out students who know they won’t live long. And we’re talking about students who are too young to vote – the age at which students pass from the institute is 18 – and yet carry guns and use them regularly. A further point to notice is that none of the students after the mid-80s belonged to General Ershad’s political party, the Jatiya Party. Whatever the demerits of the General, he preferred to deploy men with guns rather than boys with guns.

Imagine, then, a network of lawless young men, protected by the two parties for their services during hartals and agitation – in short, two private armies – and you can piece together the jigsaw of seemingly inexplicable criminal acts as the throwing of acid on women.

The thesis presented here has been criticised by feminists and leftists. Feminists in Bangladesh portray violence as largely violence against women; those with left-of-centre views suggest market-opening measures and globalisation as the cause of violence. The latter first. Bangladesh abandoned socialism after the death of Sheikh Mujib in 1975. The level of violence actually fell! Indira Gandhi and her son introduced violence and thugs to Indian politics decades before India went to the IMF cap in hand in 1991. Ethnonationalist violence there predates market-opening manoeuvres. In Sri Lanka, violence has a history as old as that of the country itself: between 1948 and 1983, there have been seven instances of mass violence in which the Sinhalese majority attacked the Tamil minority.

The most significant of these riots took place in 1956, 1958, 1977, 1981 and 1983 – that is, both before and after the economy was opened up and liberalised by the United National Party in 1977![lxiii] We noted above that there was a remarkable similarity between the riots of 1984 in India and 1983 in Sri Lanka – one ‘open, liberalised’, the other ‘closed, statist’. And violence today in Sri Lanka is not confined to the civil war – mainstream politics is thuggish and murderous.[lxix] Democracy has clearly played a decisive part in fomenting violence in South Asia.

Suppose that the free market has contributed to violence in, say, Bangladesh. We would expect farmers – always the most vulnerable group in Third World countries – as well as workers in declining industries to vent their anger in violent protest. But it is the students and the Members of Parliament working with bureaucrats who murder, rape, and burn people. Perhaps the extended family safety net is one of the reasons why marginalised workers and farmers have not taken up violent means of protest.

There appears to be no correlation between income inequality and violence – or indeed between economics and violence. In Brazil, between 1976 and 1996, inequality fell (the Gini coefficient declined from 0.62 to 0.59); Bangladesh became more unequal between 1992 and 1996, with the Gini coefficient rising from 0.26 to 0.31.[lxx] And yet violence increased in both countries. In the last decade, much of Africa became less globalised: the ratio of trade to national income fell.[lxxi] Yet we have seen that violence surged in places like Rwanda, Congo, Nigeria, Burundi, South Africa, Malawi and Madagascar. (The number of democracies in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 4 – an all-time low – in 1989 to 33 in 1995!).[lxxii] However, Kinshasa has one of the lowest crime rates in Africa. This is so despite the fact that the economy has collapsed with the regime of Mobutu Sese Seko: the Congolese franc was devalued to 23.5 to the dollar from 9, and in the black market $1 fetches over 60 francs. The government has been printing money continuously to finance the war. The calm in Kinshasa has so far been due largely to the informal network of friends and family.[lxxiii] But more on family-ties soon.

That democracy, and not globalisation, is the contributory factor behind the violence should be obvious from the fact that democracy is 2,500 years old and globalisation only 50 years old – with the most comprehensive trade round, the Uruguay round, concluded in only 1993![lxxiv] It used to be a commonplace among thinkers from antiquity onwards that democracy is an unstable and violent system, a view reinforced by the French revolution and subsequent events. As Tambiah has observed: “The general theme of whether democracy as a political process and the democratic state as a system intensify the occurrence of violence is an old one in the history of political theory. From the Greeks onwards, even up to the nineteenth century, many theorists, perhaps most, associated democracy with civil strife, and it is only subsequently that this became a minority view.”[lxxv]

Thus we have Plato’s famous lines in The Republic:

‘…those who have tasted philosophy and know how sweet and blessed a possession it is, when they have also realized the madness of the majority, that practically never does any one act sanely in public affairs, that there is no one in whom one might find an ally in the fight for justice and live – then like a man who has fallen among wild beasts, neither willing to join the others in doing wrong, nor strong enough to oppose their savagery alone, for he would perish before he could benefit his country or himself, of no use to himself or anyone else – taking all this into account, he keeps quiet and minds his own business. Like a man who takes refuge under a wall from a storm of dust or wind-driven hail, the philosopher is glad, seeing other men filled with lawlessness, if he can somehow live his present life free from wrongdoing and impiety and thus reach death with grace, goodwill and a beautiful hope.’[lxxvi]

Compare Thucydides:

‘Pericles, indeed, by his rank, ability and known integrity was enabled to exercise an independent control over the multitude –in short, to lead them instead of being led by them;…what was nominally a democracy became in his hands government by the first citizen. With his successors it was different. More on a level with one another, and each grasping at supremacy, they ended by committing even the conduct of state affairs to the whims of the multitude.’[lxxvii]

Given such events as the murder and enslavement of the Melians, the disastrous invasion of Sicily, the execution of Socrates and the fact that between 479 and 338 Athens was at war every two out of three years, with never more than ten consecutive years of peace, it is not surprising that the Thucydidean and Platonic criticisms of democracy should echo one another.

According to S.E. Finer: “The Forum polity is comparatively rare in the history of government, where the Palace polity and its variants are overwhelmingly the most common type. Only in the last two centuries has the Forum polity become widespread. Before then its appearance is, on the whole, limited to the Greek poleis, the Roman Republic, and the mediaeval European city-states. Furthermore, most of them for most of the time exhibited the worst pathological features of this kind of polity. For rhetoric read demagogy, for persuasion read corruption, pressure, intimidation, and falsification of the vote. For meetings and assemblies, read tumult and riot. For mature deliberation through a set of revising institutions, read instead self-division, inconstancy, slowness, and legislative and administrative stultification. And for elections read factional plots and intrigues. These features were the ones characteristically associated with the Forum polity in Europe down to very recent times. They were what gave the term ‘Republic’ a bad name, but made ‘Democracy’ an object of sheer horror.”[lxxviii]

Hence the obsession of The Federalist Papers with questions of safety:

“Sparta, Athens, Rome, and Carthage were all republics; two of them, Athens and Carthage, of the commercial kind. Yet were they … often engaged in wars….Venice, in later times, figured more than once in wars of ambition…

The provinces of Holland, till they were overwhelmed in debts and taxes, took a leading and conspicuous part in the wars of EuropeIn the government of Britain the representatives of the people compose one branch of the national legislature. Commerce has been for ages the predominant pursuit of that country. Few nations, nevertheless, have been more frequently engaged in war; and the wars in which that kingdom has been engaged have, in numerous instances, proceeded from the people.”[lxxix]

“It is impossible to read the history of the petty republics of Greece and Italy without feeling sensations of horror and disgust at the distractions with which they were continually agitated, and at the rapid succession of revolutions by which they were kept in a state of perpetual vibration between the extremes of tyranny and anarchy.”[lxxx]

And as late as 1927, Aldous Huxley could write:

“Only the most mystically fervent democrats, who regard voting as a kind of religious act, and who hear the voice of God in that of the People, can have any reason to desire to perpetuate a system whereby confidence tricksters, rich men, and quacks may be given power by the votes of an electorate composed in a great part of mental Peter Pans, whose childishness renders them peculiarly susceptible to the blandishments of demagogues and the tirelessly repeated suggestions of the rich men’s newspapers.”[lxxxi]

Huxley’s solution to the democratic problem was the ‘aristocratic state’ – that is, a bureaucracy. The ideal exam would select people for the task they are best suited to perform. “That every human being should be in his place – that is the ideal of the aristocratic as opposed to the democratic state. It is not merely a question of the organisation of government but of the organisation of the whole of society.”

However, since then, criticism of democracy has fallen strangely silent – democracy has indeed been elevated to the level of a ‘creed’, to use Huxley’s expression.

Feminists alter the evidence itself.

‘Imagine waking up and going to look in the mirror, only the face that stares back at you is not your face at all. It is a horribly scarred and hideously disfigured face. In a panic you try again and again to make yourself wake up, knowing the relief you will feel when [a]wake and find it was only a bad dream.

‘For approximately 200 young women in Bangladesh last year, this nightmare became a reality. Disfigured in ways that defy description – and comprehension – they were the victims of acid attacks….’

This excerpt is from the latest British Council quarterly, which included a report on an NGO called the Acid Survivors Foundation – a reply card is included for those who wish to contribute to ASF at home or from abroad. The work of the NGO is essential and invaluable; however, no NGO or groups of NGOs are capable of preventing the crime in the first place; the police as well as the victim routinely know who the perpetrator was, but he is never arrested. An acid victim spoke to the Uttara Club and told the story how she knew who did this to her but that he had not even been charged. The police dare not do anything because these people have connections in the highest places, the OC (Officer-in-Charge) merely risks being transferred to a remote corner of Bangladesh for daring to touch a party-member. One gets a measure of their immunity from law and scrutiny when one considers the fact that a ruling-party student activist openly celebrated his 100th rape at Jahangirnagar University in a cafeteria!

Foreign-funded NGOs and the foreign media refuse to make the obvious inference – for obvious reasons. The former portray violence against women as the ruthless repression of women in a male-dominated, oriental, Muslim society; the latter pick it up from there: when women are raped and repeatedly have acid thrown into their faces and the perpetrators are shielded by political parties, it is trivialising the issue to argue that women are being victimised by men.

Incidents of sexual harassment of women at educational institutions over the last few years provide a shocking pattern: the perpetrators are mostly political activists, especially those belonging to the student fronts of the mainstream political parties. – The Daily Star, 11th March, 2000

The Economist article on acid throwing in Bangladesh (January 17th, 1998) gropes for an explanation of the phenomenon. It begins promisingly with the observation, ‘According to one theory, the attacks are a dreadful manifestation of a male backlash against women improving their lot.’ The reader then expects at least one other theory, but is sorely disappointed. In the concluding line, an NGO-activist is quoted: ‘The authorities have to think of new development strategies which create jobs for men.’ There is absolutely no attempt to look at other violent crimes in society, or the rising levels of lynching, extortion, and kidnapping for ransom, let alone the role of political parties in shielding criminals and the amazingly low rate of conviction. The reader of the Economist is expected to be – and no doubt is – satisfied with this explanation. The crime has been ‘genderised’. In fact, acid attacks are no longer directed at women alone – men are increasingly victims as well (of the 315 victims of acid attacks between May and November 2000, 246 were female[lxxxii] and male victims of acid crimes by January 2003 constituted 35% of the total, up from 17% in 1999).[lxxxiii] In February 2002, the nation was reminded for the umpteenth time of the nexus between violence and democracy:

Police on Tuesday submitted charge-sheet of the sensational Mahima gang-rape case accusing four rakes of the heinous crime….They are said to be local activists of Jatiyabadi Chatra Dal, the student wing of ruling BNP.

It is stated in the charge that Mahima, 15, daughter of Abdul Hannan of Kathalbaria village in Puthiya upazilla was picked up by the accused from the backyard of her home and gang-raped by them on February 13. The rapists also took photographs of the raping scenes and exhibited those to the public to humiliate her and the family. Ultimately, the teenager committed suicide by taking pesticides on February 19 to hide her disgrace forever.[lxxxiv]

She was raped because her father and brother belonged to the opposition. People feel that the accused will get off the hook: of the four, only one has been arrested. In September 1998, a committee investigated allegations of sexual abuse at Jahangirnagar University against boys from the Chatra League, the student front of the ruling Awami League. It revealed that

more than 20 female students were raped and over 300 others were sexually harassed on the campus by the “armed cadres of a particular political party.”[lxxxv]

No charges were pressed. To quote The Daily Star:

“Over the years mainstream political parties have primed the student organisations with criminal elements in the belief that laying control on (sic) the campuses means half the electoral battle won.” [lxxxvi]

An incoherent policy makes itself apparent: the pursuit of a democratic society, on the one hand, and a society safe for women, on the other. As every undergraduate student of economics knows, law and order is a public good – it is either provided for everyone or no one. ‘Genderisation’ of crime shields the very system that spawns such violence. And the inevitable conclusion is avoided.

We either choose democracy or safety – but not both. This rather blunt proposition invites investigation. In Asia, the kind of freedom valued by the Athenians and Westerners today – the freedom from interference in what one does – is meaningless.[lxxxvii] At every stage of one’s life one is told what to do – by elders, by relatives, by non-relatives….As such, there is no ‘private life’. Democracy is, therefore, rejected in the very process of primary and secondary socialisation in Asia.

Take linguistic considerations. The Bengali translation of the verb ‘sit’ would be bosha. But translation would not reveal how the word is used. To start with, the pronoun ‘you’, which in the language usually precedes a request, discriminates carefully between equals, inferiors and superiors as ‘apni’, ‘tumi’ and ‘tui’ respectively; and so does the verb! The language reflects and reinforces the social hierarchy – and this is true of all the major languages of South Asia.

In a lighter vein, it may be of interest to note that the president of Bangladesh has launched a “Say Apni” campaign, “a social motivation programme for polite and gentle behavior.”[lxxxviii]

In a lighter vein, it may be of interest to note that the president of Bangladesh has launched a “Say Apni” campaign, “a social motivation programme for polite and gentle behavior.”[lxxxviii]

Citizens have been asked to greet strangers with “apni”, whatever their status – yet surely a democracy should encourage everyone to greet each other with the egalitarian “tumi” instead of any of the other forms! The particular form of authoritarianism – one-party system, autocracy, monarchy – is, therefore, irrelevant to the argument; authoritarianism, in some form or other – consistent with the history and culture of the nation – there must be.

Commentators such as Ayesha Jalal[xcv] and the Mahbubul Haq Centre[xcvi] have observed that democracy in South Asia is an empty ritual. Not so! Clearly, the outcome of elections is of immense significance – to politicians. The people inevitably lose. The politicians – and the middle class whom they represent – always win. The timing of India’s nuclear test can only be explained by the party-political calculations of the Bharatiya Janata Party. Vote-competition took the form of nuclear competition.

It is often commented that the Indian sub-continent – meaning Pakistan and India – can bury its differences much as Europe has done. Apart from the fact that European nation-states had a shared history and religion stretching back to the Holy Roman Empire, we must keep in mind that Europe was able to achieve peace and save its civilisation not only by rejecting nationalism, but by jettisoning democracy as well. As Larry Siedentop has observed: “The direct election of Euro MPs is itself hardly more than a fig-leaf which fails to conceal the over-sized member of the European body – the power of the European Commission and a bureaucracy imperfectly controlled by the Council of Ministers.”[xcvii]

The historian Norman Davies observes: “Hitler’s democratic triumph exposed the true nature of democracy. Democracy has few values of its own: it is as good, or as bad, as the principles of the people who operate it. In the hands of liberal and tolerant people, it will produce a liberal and tolerant government: in the hands of cannibals, a government of cannibals. In Germany in 1933-4, it produced a Nazi government because the prevailing culture of Germany’s voters did not give priority to the exclusion of gangsters.”[xcviii]

That Norman Davies finds so repugnant in the practice of democracy has already been alluded to by S.E. Finer as the ‘pathologies’ of the forum style of government above: “For rhetoric read demagogy, for persuasion read corruption, pressure, intimidation, and falsification of the vote. For meetings and assemblies, read tumult and riot”. That the pathologies are fresh in the minds of the European elite has been glaringly obvious since the Austrian election that produced a government consisting of the Freedom Party. Louis Michel, the foreign minister of Belgium, said that voters can be “naive” and “simple”. Of Jorg Haider’s Freedom Party, he says that to be a democratic party “you must work by democratic rules, you must accept not to play on the worst feelings each human being has inside himself.”[xcix]

The masses were rarely consulted, and only when the infrastructure of the European Union was firmly in place. One senior German diplomat has been quoted as saying: “If we had had a referendum on the Treaty of Rome, people might have rejected it on the grounds that it raised the price of bananas.”[c] And when they said “No” in a referendum, they were asked again and again. A paltry few bother to vote for Members of the European Parliament – because only a paltry few understand the leviathan (in the 1999 elections to the European Parliament, turnout fell below 50% for the first time, and had voting not been compulsory in Greece, Italy, Luxembourg and Belgium, turnout would probably have been 42%!).[ci]

In elite terrified of the prospect of another war conceived the entire project. The response to the pathologies of democracy in Europe was ‘consensus politics’: European leaders eschewed ideology.[cii] Finally, Huxley’s vision of a bureaucratic polity has become a reality: Europe (and Japan) are run by unelected bureaucrats, and the recent constitution has made the European Union even more inscrutable to the voter. That, perhaps, is the way to the future – the forum-bureaucratic polity or a purely bureaucratic polity (neither of which even figures in Finer’s history of government, since they have never existed) or the traditional bureaucratic-palace polity. The common element in each of these possibilities is the bureaucratic element, and the downgrading of the forum element. The less power exerted by the people, or in the name of the people, the safer the world will be.

Larry Siedentop bemoans the loss of people power. One has only to examine the legacies of the French Revolution to appreciate the dangers inherent in people power. Without the people’s sovereignty, the people’s army, the people’s language and culture – in short, the people – the First and Second world wars would have been impossible: every force unleashed by the French revolution incubated into the world wars.

According to J. M. Roberts: “Europe had, after all, been prepared for war by the first age of mass education and literacy, by the first mass newspapers, and by decades of the propagation of ideals of patriotism. When it started, the Great War, which was to reveal itself as the most democratic in history in its nature, may well also have been the most popular ever.”[ciii] For even the Social Democrats ‘blood proved thicker than water’,[cv] and they abandoned their socialism and pacifism to support their respective nations. This, despite the fact that the socialist vote was increasing; that socialist parties were becoming firmly entrenched in national parliaments: the Social Democratic Party had 1 million members, controlled 90 newspapers with a circulation of almost 1.5 million and attracted 4 million votes.[cvi] Rather, this essay would argue, it was because of their increasing contact with voters that they had to respond to the war along nationalist lines. As we have seen, the French Revolution established and sacralised the citizen-soldier-voter link.

For even the Social Democrats ‘blood proved thicker than water’,[cv] and they abandoned their socialism and pacifism to support their respective nations. This, despite the fact that the socialist vote was increasing; that socialist parties were becoming firmly entrenched in national parliaments: the Social Democratic Party had 1 million members, controlled 90 newspapers with a circulation of almost 1.5 million and attracted 4 million votes.[cvi] Rather, this essay would argue, it was because of their increasing contact with voters that they had to respond to the war along nationalist lines. As we have seen, the French Revolution established and sacralised the citizen-soldier-voter link.

Women often had a material interest in war, as well as the less immaterial ones of patriotism and nationalism. This is illustrated by their attitudes and involvement in the Paris munitions industry in 1916 and 1917: so long as the strikes were about pay, women’s participation was high; indeed, they sometimes constituted the majority of strikers. When strikes turned pacifist in early 1917, however, female participation fell. Male pacifists saw this as female betrayal – though it made sense for women, who would not be sent to the front and whose income would decline after war.[cvii]

A legacy of the revolution was the combination of the two principles of the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen’: first, the nation decides its own destiny, and, second, ‘the nation’ means the People.[cviii] The French nation was not to be a collection of individuals, but a union of persons into one family: worship of the collective self. As the historian of government, S.E. Finer observed “…the Revolution became a kind of religion, and one that everybody was supposed to share.”[cix]

The Declaration ‘consecrated the principle of election by or through the People’.[cx] The deification of the people had begun: the French people deified, the Germans soon reacted by deifying the German people. Finer quotes Heine as having anticipated Nazi Germany 100 years before the event: “There will come upon the scene armed Fichteans whose fanaticism of will is to be restrained neither by fear nor by self-interest; for they live in the spirit, they defy matter like those early Christians who could be subdued neither by bodily torments nor by bodily delights…he has allied himself with the primitive powers of nature, that he can conjure up the demoniac forces of old German pantheism….The old stone gods will arise from the forgotten ruins and wipe from their eyes the dust of centuries and Thor with his giant hammer will rise again, and he will shatter the Gothic cathedrals… [cxi]

[cxi]

One has only to note the repeated references to religion and religious feeling and imagery in the preceding paragraph – both on Finer’s part and Heine’s – to “hear the voice of God in that of the People”, to repeat Aldous Huxley’s expression.

“The mass religion of The Nation was reflected in equally mass defence.”[cxiii] The citizen army was another legacy of the French Revolution. Compare the military strength of nations before 1789 and later:

The qualitative change was no less striking: in 1914, the army consisted of nationals; not so in the eighteenth century. We, therefore, had huge numbers able to fight, and willing to kill – and be killed. Where the American War had bankrupted France and led to revolution, now it was inexpensive to employ soldiers. “Every able-bodied man regarded this, now, as a sacred duty. That is how, when 1914 came, so many millions of men went to their graves like sheep.” Or take these lines from All Quiet On The Western Front: “With our young, wide-open eyes we saw that the classical notion of patriotism we had heard from our teachers meant, in practical terms at that moment, surrendering our individual personalities more completely than we would ever have believed possible even in the most obsequious errand boy.”

Unsurprisingly, Larry Siedentop’s book Democracy in Europe is perhaps the most explicit attempt to elevate democracy to the status of religion: he identifies democracy with Christianity. “For the Christian God survives in the assumption that we have access to the nature of things as individuals. That assumption is, in turn, the final justification for a democratic society, for a society organised to respect the equal underlying moral status of all its members, by guaranteeing each ‘equal liberty’. That assumption reveals how the notion of ‘Christian liberty’ came to underpin a radically new ‘democratic’ model of human association’ (italics original). “Thus, the defining characteristic of Christianity was its universalism. It aimed to create a single human society, a society composed, that is, of individuals rather than tribes, clans or castes.”

That democracy today is very much a religion, on a par with secular creeds like Marxism and nationalism, is all too evident. Ninian Smart has adumbrated the seven dimensions of religion . We go over them in turn with respect to democracy. First, there’s the ritual dimension of the quinquennial vote, the municipal and local elections, the swearing-in ceremony….Then there’s the experiential or emotional aspect: every election is preceded by months of campaigning during which euphoria and heightened expectations prevail. The narrative or mythical dimension of democracy is fairly obvious: there’s the identification over 2,500 years with Greek democracy, with Harmodius and Aristogeiton, with the overthrow of the Peisistratids, with Cleisthenes, with the Roman Republic. Again, democracy, more than nationalism, has a far richer doctrinal dimension, ranging from – to take an arbitrary range – the treatises of John Locke to the output of John Stuart Mill. The ethical dimension: values (albeit observed in the breach) of tolerance, equality, accountability, are inculcated in voters. The social and institutional aspects of democracy stand out: there’s the elected President or Prime Minister with his or her regalia and elaborate ceremonies. The material embodiment of democracy is often magnificent: in Bangladesh there’s the Assembly Building designed by Louis Kahn; The Capitol, the White House and Westminster Palace are imposing monuments to democracy.

Two unfortunate consequences follow: the goodness of democracy becomes evidence-transcendent, like the goodness of God; and its preaching becomes an article of faith. The latter first. Richard Vinen remarks: “Some regretted the quiet, undramatic nature of most European life at the end of the century and felt that Europe had become a colourless place. ” These people included Francis Fukuyama. But he might as well have been speaking of Larry Siedentop. Democracy has no better disciple than Francis Fukuyama who lamented that “The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the world-wide ideological struggle that called for the daring, courage, imagination and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.” To die for an idea – and to kill for an idea – are virtues for Fukuyama. Vinen comments: “Those who had once ‘risked their lives for a purely abstract goal’, rather than working for the State Department and the Rand Corporation, often took a different view.”

One cannot help concluding that the proselytism inherent in the view of democracy-as-religion must inevitably lead to violence on a world-wide scale. The very universalism that Siedentop boasts as the unique characteristic of democracy, derived from Christianity (however spuriously by Siedentop*), excludes and downgrades other civilisations – a repetition of early European feelings of superiority that one thought had been eschewed among intellectual circles.